When Markets Start Thinking - The Rise of AI Agents and the End of Human-Only Economics

Explore how Demand, Supply, and Design of AI Agents transforming global markets and redefining digital economics.

A new kind of participant is entering the global economy - one that doesn’t sleep, negotiate pay, or tire from comparison shopping. These are AI agents: autonomous systems that can perceive, reason, and act on behalf of humans.

A recent paper by economists from MIT, Harvard, and BU explores how these agents could transform markets by dramatically reducing transaction costs - the hidden frictions of searching, negotiating, and contracting that shape nearly every business activity.

The authors argue that AI agents are not just tools, but market actors in their own right - capable of transacting, reasoning, and learning across digital environments.

For business leaders, this research provides an early map of how markets might reorganize around AI. Just as the internet redefined access to information, AI agents could redefine access to action - executing decisions for individuals and organizations alike.

Demand for AI Agents

Why People Will Use AI Agents

Humans will turn to AI agents for the same reasons they hire human ones - to save time, gain expertise, and preserve privacy.

These motivations will drive two main types of adoption:

Substitution - replacing human intermediaries such as recruiters, brokers, or advisors.

Expansion - enabling transactions that were previously too costly or complex to pursue.

By converting time and cognitive effort into low-cost computation, agents unlock new possibilities across industries. They can compare thousands of insurance offers, schedule services, or negotiate contracts faster and cheaper than people can.

Where Adoption Will Start

AI agents will likely gain traction first in markets already dependent on human intermediaries or digital platforms - places where high stakes, complex options, and large counterparties exist.

Think of real estate, hiring, or investment advice. On platforms like LinkedIn, Zillow, or Upwork, agents can search and negotiate tirelessly. Over time, this may shift market power toward consumers, as agents act purely in their principal’s interest - rational, data-driven, and free from fatigue or bias.

What People Will Expect

Just like human professionals, users will want AI agents that are capable, informed, and loyal. They must understand intent, act ethically, and remain aligned with their user’s goals.

Trust will become a key differentiator. Users will compare agents based on benchmarks, transparency, and performance reputation, not just price or speed.

Designing AI Agents

Designing AI agents involves both engineering and economic challenges.

On the technical side, the goal is to build systems that can perceive, reason, and act reliably across digital contexts. On the economic side, the challenge is alignment - ensuring that agents act according to their user’s true preferences.

Understanding Human Preferences

A core difficulty lies in figuring out what people actually want.

Traditional recommendation systems infer preferences from limited signals like clicks or ratings. But AI agents operate in open-ended natural language, allowing them to handle far more complex goals - and far more room for misunderstanding.

Users may struggle to articulate their real preferences, while agents may misinterpret or hallucinate them.

In high-stakes decisions - like buying a home or making an investment - even small misinterpretations can have major consequences.

Balancing Autonomy and Oversight

Agents must also learn when to act on their own and when to consult the human.

Too much autonomy risks unwanted outcomes; too little wastes the agent’s potential. The authors refer to this balance as meta-rationality - knowing the limits of one’s own reasoning.

As agents interact in markets, they’ll face adversarial manipulation - attempts by others to exploit their logic or decision rules. Designing for robustness, transparency, and clear delegation boundaries will be essential to maintaining trust.

Supply of AI Agents

On the supply side, two forces shape the emerging agent economy:

How agents are produced and priced

How they are owned and specialized

From Foundation Models to Market Products

Most agents are built on foundation models - large, general-purpose systems like those developed by OpenAI or Anthropic.

This structure creates two tiers of suppliers:

Model owners, who build and control access to foundational systems.

Agent developers, who customize these systems for particular industries or functions.

Since the cost of producing each additional agent is close to zero, supply is effectively unlimited. However, compute and data requirements mean high-stakes or domain-specific agents could still carry higher costs.

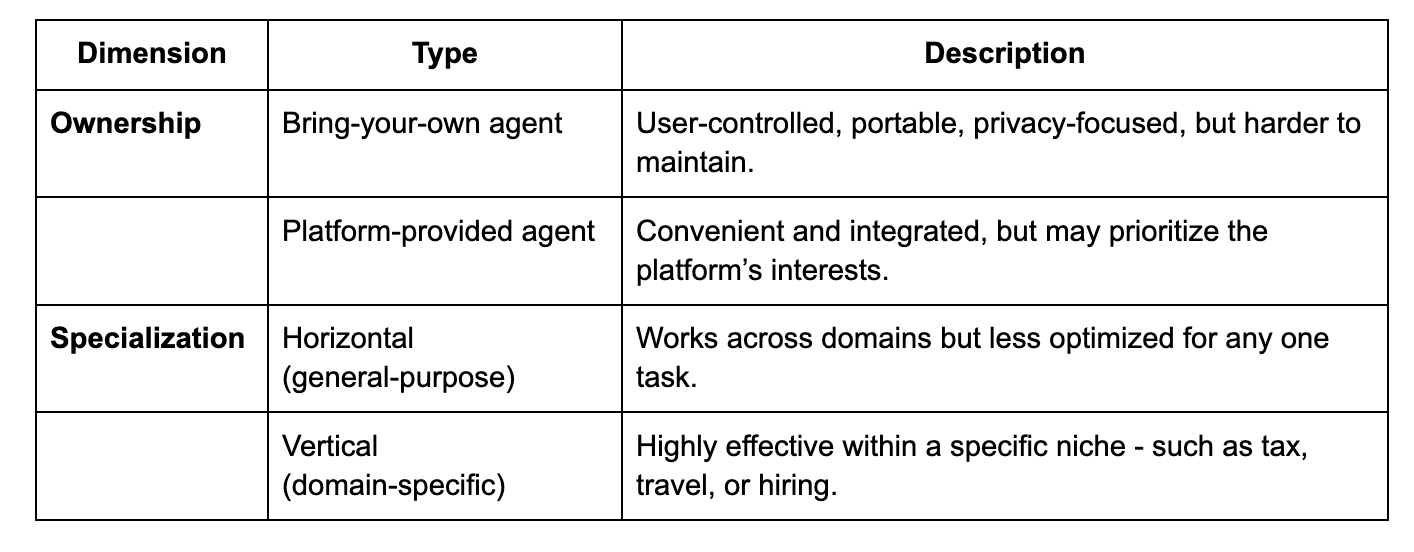

Ownership and Specialization

Consumers will encounter agents that differ by ownership and specialization.

Each combination carries trade-offs between alignment and convenience.

A user-owned vertical agent may best protect interests but require setup and cost. Platform agents will be easier to use yet may deepen lock-in and self-preferencing, reinforcing today’s platform power dynamics.

Market Design for AI Agents

As agents proliferate, markets themselves will need to evolve - not only through policy but through how participants are identified, trusted, and coordinated.

Identity and Accountability

Distinguishing between humans and machines will become vital.

The authors emphasize the need for digital identity systems that verify both humans and their AI representatives.

Two models could emerge:

Walled gardens, where platforms tightly control verification and participation.

Open systems, using cryptographic proofs or digital IDs for universal recognition.

“Proof-of-personhood” systems could ensure one verified identity per human, protecting markets from mass automation and manipulation.

Rethinking Platform Economics

AI agents will also disrupt how digital platforms earn revenue and compete.

Today’s platforms monetize human attention - optimizing for clicks, engagement, and emotion. But AI agents don’t click or scroll. They act rationally, filtering content and making decisions without distraction.

This shift could undermine attention-based business models, pushing platforms toward subscriptions, utility-based pricing, or machine-to-machine APIs.

Over time, the internet may divide into two layers:

A human web designed for people.

An agent web optimized for autonomous systems.

Enabling New Market Mechanisms

AI agents could also enable new kinds of market mechanisms that were once too complex to implement.

For example, job or housing markets could move from simple recommendations to equilibrium matching, where agents representing both sides exchange structured preference data to reach optimal matches.

Agents could even enhance privacy and fairness, negotiating sensitive details without revealing personal information.

If designed responsibly, they could make markets more efficient, transparent, and personalized than ever before.

Final Words

The rise of AI agents marks a pivotal moment in how economies are organized.

By automating the costs of searching, negotiating, and coordinating, these systems can make markets faster, fairer, and more inclusive. Yet efficiency also brings risks - congestion, opacity, and power concentration among dominant platforms or model owners.

The outcome will depend on how demand, supply, and regulation evolve together.

Businesses that adapt early to an agent-first economy - where decisions and transactions are handled by intelligent digital counterparts - will gain an advantage.

AI agents are not just tools within markets; they are becoming participants in the market itself.

For leaders, the challenge ahead isn’t just adoption - it’s understanding how these agents will change competition, collaboration, and the very logic of value creation.

Read the full paper “The Coasean Singularity? Demand, Supply, and Market Design with AI Agents,” by Peyman Shahidi, Gili Rusak, Benjamin S. Manning, Andrey Fradkin, and John J. Horton (MIT, Harvard, BU, and NBER, 2025).

https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c15309/c15309.pdf